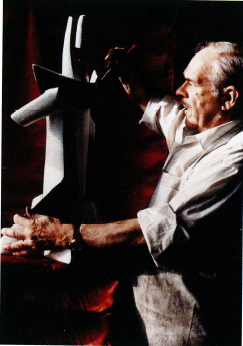

Photo: Andrij Paschuk (1926 – 2013)

“None of the sculptors since Rodin made a greater impact in his time like Archipenko. It was in the first decade of his artistic life that he created new laws of modern sculpture and rose in art history as a leader of the art revolution and drew in many others.”

“Svyatoslav Hordynsky, Ukrainian artist, poet, and writer.

Every book about twentieth century art mentions Alexander Archipenko. While alive, he was acknowledged as one of the most acclaimed sculptors in the world. His works are in collections at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, MoMa and Guggenheim Museum in New York, and at museums in Stockholm, Berlin and Tel-Aviv. Archipenko is a national artist in France, Germany and the United States where he lived and created. Notwithstanding this, with his unique art, he raised awareness of Ukrainian culture to a higher level more than any Ukrainian diplomat could have.

Archipenko was born in Kyiv, Ukraine in 1887. After studying painting and sculpture at Kyiv Art School, in 1908 he briefly attended the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. However, he quickly abandoned formal studies to become part of more radical circles, especially the Cubist movement. He began to explore the interplay between interlocking voids and solids and between convex and concave surfaces, forming a sculptural equivalent to Cubist paintings’ overlapping planes, thus revolutionizing modern sculpture. In his bronze sculpture Walking Woman (1912), for example, he pierced holes in the face and torso of the figure and substituted concavities for the convexities of the lower legs. The abstract shapes of his works have a monumentality and rhythmic movement that also reflect contemporary interest in the arts of Africa.

As he developed his style, Archipenko achieved an incredible sense of vitality out of minimal means: in works such as Boxing Match (1913), he conveyed the raw, brutal energy of the sport in nonrepresentational, machinelike cubic and ovoid forms. About 1912, inspired by the Cubist collages of Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso, Archipenko introduced the concept of collage in sculpture in his famous Medrano series, depictions of circus figures in multicolored glass, wood, and metal that defy traditional use of materials and definitions of sculpture. During that same period he further defied tradition in his “sculpto-paintings,” works in which he introduced painted color to the intersecting planes of his sculpture.

Archipenko was represented in the New York Armory Show of 1913 and in many international Cubist exhibitions. In 1921 he moved to Berlin and opened an art school. During that time his works were as famous in Europe as those of Picasso.

In 1923, Archipenko immigrated to the United States. He established an art school in New York City, and in the following year, moved it to Woodstock, NY. Showing his broad interests and widely inventive mind, he created and received a patent for changeable pictures (peinture changeante) known as Archipentura and Apparatus for Displaying Changeable Pictures. Besides working at his art, Archipenko devoted much time to teaching. He was in constant contact with various universities, among them those in Oakland, Los Angeles, Seattle, and Chicago (the New Bauhaus School). In 1927 an exhibition of his works was arranged in Tokyo. In New York, he established a school of ceramics, Arko. In the 1930s, his work appeared in the Ukrainian Pavilion at the Century of Progress Exposition in Chicago. In 1947, Archipenko created the first sculptures out of transparent materials (plastics) with interior illumination (modeling light). In the following years, Archipenko tried his hand at moving figures, which were mechanically rotating structures built of wood, mother of pearl, and metal. At Biennale d’Arte Trivenata in Padua, Italy, he received the gold medal. In later years, he again concentrated on industrial materials, in which he demonstrated his taste for dazzling polychromy. Juan Gris wrote about Archipenko’s influence on the art of the early 20th century: “Archipenko challenged the traditional understanding of sculpture. It was generally monochromatic at the time. His pieces were painted in bright colors. Instead of accepted materials such as marble, bronze or plaster, he used mundane materials such as wood, glass, metal, and wire. His creative process did not involve carving or modeling in the accepted tradition but nailing, pasting and tying together, with no attempt to hide nails, junctures or seams. His process parallels the visual experience of cubist painting.”

Archipenko never severed his ties with his countrymen. During his first years in Paris he was a member of the Ukrainian Students’ Club; in Berlin, a member of the Ukrainian Hromada; and in the United States, a member of the Ukrainian Artists’ Association in the USA. He belonged to the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences and was an honorary member of the Ukrainian Institute of America where he was exhibited multiple times.

Archipenko died February 25, 1964, in New York.