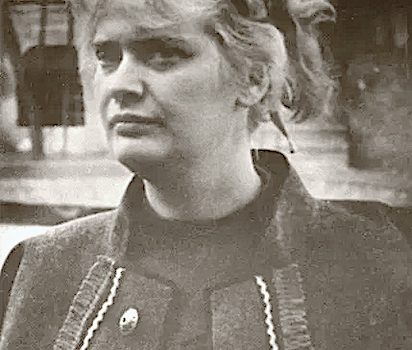

Today, November 28, 2020 marks the 50th anniversary of the brutal murder of Ukrainian artist, human rights activist, mother, and wife, Alla Horska. Dubbed “The Soul of the Shistdesyatnytstvo*,” she possessed the rare courage and strength of character needed to resist a repressive communist regime, and with sustained obstinacy defended the consciousness of truth and civil liberties.

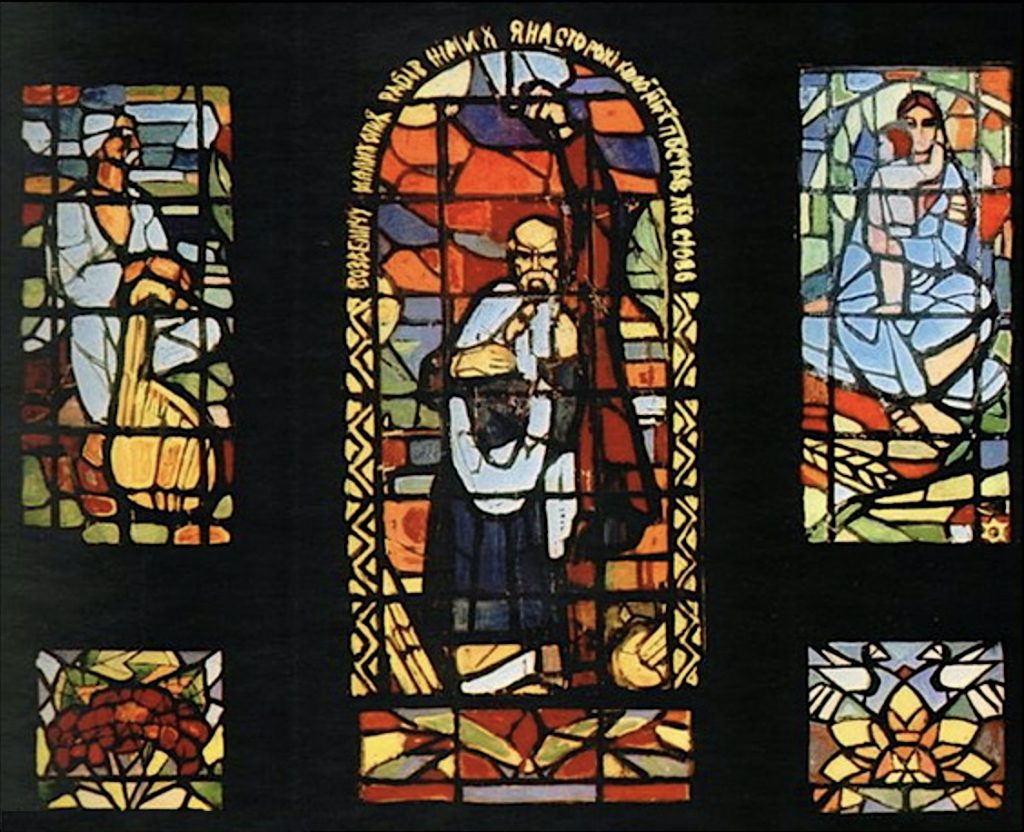

Horska is best known for her artistic collaborations on murals, mosaics, stained glass, portrait paintings and the dissemination of samvydav (self-published literature). Due to the nationalistic subject of her art, Soviet apparatchiks and KGB operatives often destroyed, deterred, and even banned her work from public display. She was expelled multiple times from the Union of Artists of Ukraine for it, leaving her professionally blacklisted in Kyiv, seeking paying project work in the industrial Donbas. Horska also dedicated much of her time to supporting fellow artists, writers and journalists who had been arrested and convicted for “anti-Soviet propaganda and agitation,” often giving vehement court testimony on their behalf and offering and raising moral and material support to their families while they were in labor and concentration camps.

Highly intelligent, motivated, and talented, the Yalta-born Horska graduated from art school with honors and later joined the Kyiv Art Institute. It was through relationships developed there, including the meeting of her future husband painter Viktor Zaretsky, that she became involved with the Creative Youth Club “Suchasnist,” the center of Ukrainian culture in Kyiv. In the early 1960s Horska joined the national revival movement in Ukraine which counted numerous intellectuals and artists of her generation, among them, Lina Kostenko, Yevhen Sverstiuk, Ivan and Nadia Svitlychny, Vasyl Symonenko, and Les Taniuk.

Though she had been raised in a Russian-speaking family (her parents were thoroughly russified), Horska embraced speaking and writing exclusively in Ukrainian under the tutelage of journalist Nadia Svitlychna. She was a fiery student of Ukrainian history and its cultural legacy, in particular folk art, academic and monumental painting, and the avant-garde of the beginning of the century. Her many and long correspondences with artist and activist Opanas Zalyvakha led to a close kinship and creative partnership rarely seen in artistic circles. Despite the harassment and artistic limitations in ideologically regimented Soviet society, Horska remained an independent soul with European values.

On November 29, 1970, Alla Horska was found dead in her father-in-law’s house in Vasilkiv, Kyiv Oblast where she arranged to collect an old family sewing machine. The investigation, led by the Kyiv prosecutor’s office, concluded that Horska’s father-in-law had killed her out of personal animosity, and then committed suicide. However, from the outset, friends and acquaintances suspected political murder at the hands of the KGB for her sustained activism. An independent investigation in the 1990s revealed an incomplete criminal file ridden with contradictions carried out with falsifications. Although the case remains officially unsolved, no one has any serious doubt as to who was responsible for Horska’s death.

Alla Horska was buried at Berkivtsi Cemetery in Kyiv on December 7, 1970, under the watchful eye of the KGB. Parting words and eulogies were pronounced by Oles Serhiyenko and Yevhen Sverstiuk. Vasyl Stus read a poem “on behalf of the residents of Lviv” and Ivan Hel spoke a farewell word in memory of “Alla Horska – a patriotic daughter of the 1960s Ukrainian revival.” Afterward, each of the forementioned intellectuals and activists was regularly harassed and threatened for their participation in this “nationalist” funeral.

Horska left a sizeable artistic heritage represented by portraits of major figures of the “Shistdesyatnyky,” in-situ mosaics, and academic studies. Her works are housed in the collections of the National Art Museum in Kyiv, the National Museum in Lviv, the Central State Archive Museum of Literature and Art, the Museum of the Sixtiers, the Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection of Soviet Nonconformist Art at Rutgers University, and the Checkpoint Charlie Berlin Wall Museum, among others.

* Shistdesyatnyky (literally, those who lived in the sixties) — a group of literati, artists and scholars of the 1960s in Ukraine who, publicly and artistically acknowledged the criminal nature of the soviet communist system and rejected dogmas of ‘socialist realism.’ Their aim was to preserve Ukraine’s culture and language through art, essays, and literature.

Andrew Horodysky

November 2020